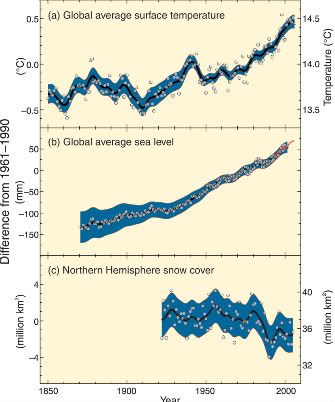

On BMG a few weeks ago, a fellow cape codder (PP) mentioned that he’s not sure he believes in climate change. That took a little bite out of my faith in humanity, or more realistically, made me start thinking seriously about scientists’ continuing difficulty in getting the message across. So since a picture is worth a thousand words: from the 2007 IPCC report:

Here's a figure about the rise in atmospheric CO2 concentrations and projections under different CO2 reduction scenarios (from Pacala et al 2004):

When I give talks to school classrooms, I do a little class participation exercise that goes like this: atmospheric CO2 was ~280 ppm (parts-per-million) prior to the industrial revolution a few centuries ago. It is now ~384 ppm. What do they think it should be for a sustainable level? They usually give me numbers in the 250-300 range. Then I show this figure, and point out that we’re running higher than the black line, business-as-usual (worst case scenario). Given the inertia of trying to move away from fossil fuels, CO2 is likely to double pre-industrial levels to 450-500ppm within their lifetimes with significant efforts. If we continue to do nothing it could very well reach as high as 700 ppm. This exercise seems to work well to get the message across.

Back to the NYT Op-Eds: There’s been a lot of dumping lately on the big three US automakers for not producing fuel efficient cars. But that’s revisionist history, over the last few decades Americans have been wanting those bigger SUVs creating the demand. We, the American consumers, are the other dancing partner in our gluttonous use of fossil fuels for transportation. The big three have been happy to oblige – SUVs have a big profit margin. Plus even Toyota has been in the big vehicle game. Sure they developed the Prius and some great hybrid technology, but they hedged their bets with the popular Tundra truck. There is simply no other policy action that would be as effective in reducing US fossil fuel emissions in the near future as increasing the gasoline tax. And it should be revenue neutral, using those funds to reduce income taxes to build popular support. From the NYT Editorial:

Americans did not buy enormous gas guzzlers just because Detroit marketed them relentlessly. They bought them because they wanted big cars — and because gas was cheap. If gas stays cheap, Americans would be less inclined to squeeze their families into a lithe fuel-efficient alternative.

Furthermore, even if the government managed to convert General Motors, Chrysler and Ford to the cause of energy efficiency, cheap gas could open the door for a competitor — Toyota, perhaps? — to take over the lucrative market for gas-chuggers, leaving Detroit’s automakers eating dust once again.

Americans have flirted with fuel-efficient cars before only to jilt them when gas prices fell. In the late 1970s, for instance, they spurned light trucks as gas prices doubled. But as gas prices declined between 1981 and 2005, the market share of sport-utility vehicles, pickups, vans and the like jumped from 16 percent to 61 percent of vehicle sales in the United States.

Personally I find it hard not to feel like a broken record on this subject of carbon taxes, but as a scientist I think its easy to forget that the public isn't looking at the data every day, and they're also thinking about many other important issues. Here's a great cartoon by Justin Bilicki (via the Union of Concerned Scientists ) capturing this sentiment.

And a nice quote to sum it up from Ray at NPR's Car Talk:

I'm sick of people whining about a lousy 50-cent-a-gallon tax on gasoline! I think its time has come, and I call on all non-wussy politicians to stand with me, because our country needs us.

An increase in the Gasoline Tax is just one of the tools in the toolbox. It gets the biggest bang for effort in reducing climate change impact right now. This is just the beginning though: We're going to need many such tools to get this problem under control.